|

Life as a Doctor in the Early Colony

Dr Andrew Nash (1833-1885)

| Dr Andrew Nash was born in Doneraile in the County of Cork, Ireland in 1834. Doneraile's claim to fame is the creation, in 1752, of the horse race called the steeplechase. It began as a race from the steeple of St John's Church in Butteworth to the steeple of St Mary's church in Doneraile. |

© Paul Holloway, Leeds, UK |

Andrew was the son of John Nash. It would appear that his family was well-to-do as a John M Nash esquire, of Bellevue, in the nearby town of Mallow, is listed under Nobility, Gentry and Clergy in the 1842/3 Pigot's Directory. Mallow, at the time had four doctors listed under Physicians & Surgeons and four under Apothecaries. Andrew Nash began his medical training with an apprenticeship to one of these, Dr Philip Barry, a popular surgeon/physician/apothecary in Main-street, Mallow1.

This was the time of the Great Irish Famine ("the potato famine"). It began in about 1845 at which date Andrew Nash was 11 years of age. The famine ended in 1849 when he was 15. The ten years following this saw mass evictions of peasant farmers from their land. This resulted in a mass exodus of people from Ireland: about 20 to 25% of the population. Whilst many left for North America, substantial numbers came to Australia, aided by immigration schemes that sometimes paid for their fares. Fares were at times also paid by family members who had already arrived in Australia. Also, in the peak of the Great Irish Famine, large numbers of young women were "exported" from the workhouses for the poor. Migration from Ireland to Australia increased dramatically with the discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851.

Following his apprenticeship, Andrew Nash obtained his Licentiate Society of Apothecaries (LSA) and the Licentiate Midwifery Society of Apothecaries in Dublin in 1857, then the Licentiate Royal College of Physicians in London in 1864, Licentiate Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons (LFPS) and the Licentiate Midwifery Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons Glasgow in 18642.

It should be noted that apothecaries, although originally a guild of practitioners who supplied medicines, won the right to prescribe as well as dispense, after the Rose case of 1704. They became, in essence, general practitioners and were licensed to practice via the LSA. Male midwives or accoucheurs, were doctors who had received formal training in midwifery. They had become somewhat dominant in the late seventeenth century. By the late eighteenth century, female midwives were regaining the popularity that they had previously had for thousands of years once their training changed from learning by observation to a more formal system of learning.

At this time in history the stethoscope, invented by Laennec in 1816, was put to use in obstetrics. It was initially used for diagnosing pregnancy. It use had been discovered and promoted by Dr J C Ferguson, who presented the paper Auscultation: the only Unequivocal Evidence of Pregnancy in Dublin in 18303.

Dr Andrew Nash became an assistant to Dr Palmer, perhaps Dr James G. Palmer, apothecary (LSA Ireland, 1840), of 127 Parade Quay, Waterford, Ireland. Nash worked there until 1857.

Dr Andrew Nash married Margaret Brady (1835-1885) on 28/2/1857 in Clonmel, Cork, Ireland. He left Ireland on 28/4/1857 on the Samuel Locke as a ship's surgeon, to seek his fortune in Australia. On the voyage from Liverpool to Melbourne his son John Brady Nash was born on 19/5/1857 near the Canary Islands (shipping record says 15/5/1857). Many of the Irish travelling in these times were suffering from the effects of starvation. This increased the mortality rates for the voyages to Australia. The Samuel Locke took 118 days to reach Australia. There were two recorded deaths for the voyage which transported 234 passengers and 24 crew members. One death was from diarrhoea and the other from suicide.

Dr Nash and his very new family arrived in Melbourne on 25/8/1857. Another child was born to them in 1858 but it died soon after. Nash and his family moved to Kilmore in Victoria in the midst of the gold rush and worked there for some years. He was appointed as a magistrate (JP) on 10/10/18594. A Justice of the Peace back then had many responsibilities and could determine penalties in minor cases and determine who would go to court. Dr Nash was appointed coroner for the Jordan Gold Field in 18625. While in Kilmore another child was born but did not survive. Nash, his wife and son moved to Jamieson, Victoria, a new gold mining town. There, in 1862, their son Andrew was born and in 1865 their daughter, Elizabeth. Nash St, which persists to this day, was named after him.

The family later moved to Woods Point, a new town which had started after the discovery of gold there in 1861. This made them some of the earliest pioneers of the gold rush there6. By 1871 the town had grown to a population of about 2,000 with 50 large mines, 30 hotels and a hospital7.

In 1864 Nash was one of the supporters for the establishment of a tram to Woods Point. The tram, however did not eventuate. In the same year the Woods Point residents commenced fund raising to build a hospital. By June 1865 the hospital had been built. Dr Nash and a Dr Solomon Iffla were the physicians and Dr Thomas Howard was the resident surgeon. Iffla had come from Jamaica, having bee born in Kingston in 1820. A challenge was made regarding the qualifications of Dr Nash and his contributions to the hospital and whether he had empathy for the miners. This was strongly opposed by the three doctors but in the process Dr Howard decided to resign8. In 1865 Nash was on a committee to establish the Woods Point Common School.In 1865 Nash became one of the nine inaugural council members for the Borough of Woods Point. During his time in Woods Point, Nash became the editor of the local newspaper, The Woods Point Times. This newspaper competed for a while with The Woods Point Mountaineer, but the small town could not support two newspapers, two journalists and two editors, so the newspapers merged in 1865 to form the Times and Mountaineer. Nash remained an editor, but had a falling out with the other editor, Alfred Goulding and so left and formed his own newspaper, The Woods Point Leader. Antipathy between the two editors lead to some acrimonious editorial battles. Lloyd, in his book Gold in the Ranges, describes the conflict as between “the impetuous young Catholic medico and the older C of E Scottish reformer”9. In 1866 Nash was charged with "criminal libel" by the editor of the Times and Mountaineer, although the charges were later dropped10.

Soon afterwards Nash was charged with assault with intent to commit rape by one of his patients. He had called in at her home a day after she had consulted him. She gave evidence that he had been slow to respond to her refusal of his amorous and forceful advances. The trial was concluded on 26/3/1866 with a verdict of not guilty. It was clear from evidence given that he had overstepped professional boundaries, but he was considered not guilty perhaps because there was no evidence that he had intended to commit rape.

In 1866 Dr Nash resigned his position of Territorial Magistrate11. Nash also did not stand for re-election for council in 1866, no doubt as his popularity was at a low ebb. In 1866 he was listed in the Wise Post Office Directory as "Nash, Andrew, M.D., J.P., M.B.C., M.R.C.S., physician and surgeon, Bridge St, Woods Point". He was one of two surgeons for the town and worked at the Upper Goulburn Hospital.

In 1867 he was elected to the Woods Point Borough Council12 in the midst of much turmoil within the Council.

Nash's love for horses was apparent in 1871 when he was the starter for the Upper Goulburn races at Jamieson.

In 1875 he was at Woods Point and working a a surgeon at the Upper Goulburn Hospital13.

|

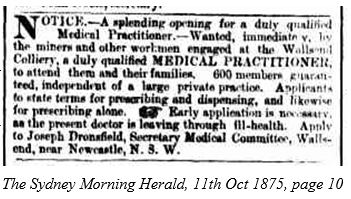

Towards the end of 1875 he applied for the position of doctor to the employees of the Co-operative Colliery in the Hunter Valley in NSW and was accepted in November of the same year.

The advertisement guaranteed 600 patients. He later also took up the position of medical officer for the Minmi collieries as well14.

On 3/1/1876 he was registered as a medical practitioner in NSW15. He became the government medical officer and vaccinator in 1876 and also took up the position of honorary member at the Newcastle Hospital16.

|

In those days the doctors did everything medical. This included attending patients in hospital and at home. Travel to home visits would have been by horse, either horseback or buggy. As Andrew Nash was an accomplished rider it is most likely that he travelled by horseback most of the time when not with his family.

One of the duties was to perform the post-mortem examinations and present findings to the coroner. Examples included

• the death of a four year old boy, Albert Harris, who fell onto a burning log in 1884 and died as a result

• James Semmens, a seven year old boy who fell into a creek and drowned17

• Mrs Ann Tildesly, who died of liver failure18

• William Taylor who died in 1882 from a rock fall in the Wallsend pit20

There were also court attendances in which he was required to give evidence as in the case of Mr Edwin Coulter in 1878 who had been stabbed seven times21.

Doctors in this era practised in a time when there were no antibiotics and multiple illnesses could cause epidemics such as typhoid, cholera and influenza. This meant that they played a role in public health as well in order to stop the spread of these diseases.

It was not uncommon for medical practices to do their own dispensing. Dr Nash employed a Mr Joseph Stapleton, to do his. Joseph later travelled to Edinburgh to study medicine and returned to the colony to work, eventually returning to Wallsend to work in Dr Nash's clinic although too late to work with Dr Andrew Nash as he had died in the mean time.

In those days there was often no option but to treat one's own family. Dr Nash's only daughter, Elizabeth, fell whilst riding one of her father's horses. She was described as being "insensible" and in a "very critical condition"22. Fortunately she recovered fully.

It was not uncommon for doctors to have significant other interests. Dr Nash was remembered as a "great sportsman"23 and was very interested in horse racing and particularly in the steeplechase. He was a member of the Newcastle Jockey Club, of which he was at times the chair and at all times an energetic supporter. He was also a member of the Northern Hunt Club24. Perhaps he had an interest in rowing as he also donated a trophy to the Wallsend and Plattsburg Regatta Club25.

Dr Nash was also a financial partner in two breweries, one in Tamworth and one in Armidale26.

Dr Nash was also an active member of the local School of Arts (from its inception in 1879) and the Mechanics Institute. He was the chairman of the directors of the W & P Gas Company, which commenced in 1883. He was also a director of the Great Northern Coal Company27.

In 1880 Dr Nash was living at his practice in Nelson St, Wallsend and was the doctor for the two collieries at Plattsburg and Wallsend.

In 1883 there was a banquet and dance held for his son who returned from his studies in Edinburgh with high honours28.

1884 his wife Margaret died after a long illness. She was buried in the Sandgate Cemetery. The funeral procession was a mile long29.

Dr Nash's interest in horse riding led to his demise at the age of 51. He was training his favourite horse, “Satellite”, for the steeplechase when it missed a hurdle, fell and crushed his chest, causing immediate death. His own son was the doctor to perform the post-mortem examination.

| The funeral was a large affair held on 22/11/1855 with about four thousand people attending. The procession was led by the Wallsend Band, followed by the Wallsend and Lambton Volunteer Infantry. Next was his horse, "Satellite", led by its jockey and the various carriages containing family and most of the medical fraternity in the district. In all there were about 100 horse drawn vehicles and 400 to 500 horsemen. Even his funeral caused controversy: the Catholic Priest failed to turn up30. As a result, the service was given by a representative of the Independent Order of Oddfellows, Manchester United (IOOF, MU). He was buried in the same grave as his wife at Sandgate cemetery. |

|

In one of his obituaries he was described as "a friend of all - rich and poor - as a sportsman who loved sport for its invigorating and exciting influence, and for the amusement it caused the people; as a magistrate who always dealt out even handed justice to all; as a man in every sense of the word, and as a citizen with a large warm heart; as a doctor, whom everyone loved for his skill, kindness and unremitting attention when sickness or care racked the brain and shattered the constitution. Dr Nash can ill be spared, and it will be a long before we shall look on his like again"31.

Dr Andrew Nash was survived by three children, two of whom went into the medical profession.

References/Notes

1. Slaters Directory of Munster, 1856, p22

2. These are listed in the NSW Government Gazette, 29/1/1877, p419. It will be noted that Dr Andrew Nash had travelled to Australia in 1857 so it is unclear how he could claim the later qualifications.

3. Ferguson JC. Auscultation: the only unequivocal evidence of pregnancy. Dublin Med Transact. 1830;i:64.

4. Victorian Government Gazette, 14/10/1859, p2177

5. Victorian Government Gazette, 22/7/1862, p1251

6. Kalgoorlie Miner, 7/4/1905, p8

7. Jamieson and District Historical Society, Woods Point, http://home.vicnet.net.au/~jdhs/8woodspoint.htm, accessed 19/2/2020

8. Lloyd, Brian, Gold in the Ranges Jamieson to Woods Point, Histec Publications, Brighton East, Vic., 2002

9. Lloyd, Brian, Gold in the Ranges Jamieson to Woods Point, Histec Publications, Brighton East, Vic., 2002, p. 85

10. Ovens and Murray Advertiser, 8/2/1866, p2

11. Victorian Government Gazette, 27/3/1866, p694

12. The Age (Melbourne), 6/9/1867, p7

13. The Medical Directory, UK and Ireland, 1875, p1088

14. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 23/11/1885, p2

15. NSW Government Gazette, 29/1/1877, p419

16. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 23/11/1885, p2

17. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 20/9/1884, p4

18. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 4/11/1884, p3

19. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 25/4/1883, p3

20. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 4/7/1882, p2

21. The Sydney Morning Herald, 13/5/1878, p5

22. The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser, 6/7/1882, p2

23. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 20/11/1933, p6

24. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 23/11/1885, p2

25. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 17/1/19434, p10

26. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 23/11/1855, p2

27. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 23/11/1885, p2

28. The Sydney Morning Herald, 17/2/1883, p12

29. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 17/2/1885, p2

30. The Protestant Standard, 5/12/1885, p8

31. Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate, 23/11/1885, p2

|

|